There’s going to be a major news story soon about fraudulent voting in Chicago and it's all my fault. That was my vote that’s about to cause all the trouble and I cannot tell you how sorry I am for the whole thing. For what it’s worth, I blame the system. I was going to do this the easy way, with a mail-in ballot. Yeah, I read about that lazy bum of a postal worker in New Jersey who tossed nearly 2,000 pieces of mail, including 99 ballots, into the trash. And I know about that now-departed election worker in Pennsylvania who threw away nine ballots because, well, just because. That wasn’t enough to deter me, though. We know about these cases because the lost ballots were found and the votes will be counted. So the system seems to be working, at least as far as finding and correcting mistakes is concerned. I cannot vote by mail, however, because I would need to sign the envelope and my signature would be checked against the one on file from 1972. Absolutely nobody would compare my flowing script from youth with the flat-lined EKG that creaks from my arthritic hand today and say, “Yep, same guy.” Any mail-in ballot from me is guaranteed to be rejected. So my only choice was to vote in person, and that’s where the fraud occurred. I stopped in at the Voting Super Center on Clark and Lake, filled out the form, and took my ballot to the machine. I was ready this time. Most elections, I punt on the judicial ballot and guess at the advisory votes. This year, though, I researched everything and voted like I was making a how-to video for the Board of Elections. After checking my ballot about six times, I went up to the Official Pointing Person to find out where to take it. True to his mission, he didn’t say anything, but he did point to a machine about 20 feet away, so I walked over and checked it out. The screen said to insert my ballot, which I did, and then a woman came running over. “You can’t do that,” she yelled. “I can’t do what?” “You can’t put that in there.” “But it said to insert it here.” “You’re not allowed to do that.” Etcetera. Because, as it turns out, I was not supposed to insert my ballot into the machine with the LCD display that said “Insert ballot.” Nope. I was supposed to wait for an election judge to come by and initial the ballot and then handle the insertion for me. In fairness, it was a small screen, but maybe they could have had it say, “Wait for election judge,” instead of “Insert ballot.” The agitated woman, who might or might not have been an election judge herself, insisted that my vote would not count, because the ballot did not have the requisite initials. I had submitted an illegal ballot and now the entire election is rigged. I explained that the official pointer had pointed me to the machine and he didn’t say I needed to wait for anyone. To no avail, of course, because I had just screwed up what is supposed to be the most important election of our lifetimes. I cannot believe I am the only one to make this mistake, which means there’s a major scandal brewing here. Someone’s going to find out about the ballots that somehow got into the machines in Chicago without a judge’s initials. (Well, you just found out because I told you.) And when people find out about it, nobody is going to say, “I guess there was some go-getter, take-charge, rugged individual who simply got the job done without waiting for some government bureaucrat to tell him it was okay.” Nope. They’re going to say, “It’s Chicago. Vote early and often. Fraud. Fraud. Fraud.” And it’s all my fault. I am so, so sorry. I promise that I will get it right when I go back to vote again next week. JK. Of course I’m not going to vote again next week. Or am I? The only way to find out is by subscribing to our weekly posts by clicking here.

0 Comments

Finally, finally, finally, finally, finally, a Halloween worthy of celebration. Even the darkest of clouds has a silver lining and this infernal pandemic is giving us a reason to celebrate at last. Regular readers know that I’m a true expert on Halloween, especially when it comes to techniques for getting the best candy with the least aggravation. It’s a game for chess masters as parents strategize the optimal routes for their children and try to psych out their neighbors to score full-size Snickers in exchange for a roll of Smarties. Not so this year, though. With social distancing and hygiene concerns, millions of kids are giving up on the idea of standing six feet apart to wait for a Junior Mint that mom will insist on sterilizing in the microwave. Millions of people are standing in line for hours to cast their ballots this year, but how long is anyone really going to wait for some Candy Corn? Huzzah!!! Finally, on a holiday that’s really about the parents, we can celebrate without guilt and without all the craziness. With so many families opting out of the traditional tricking and treating, it’s a breeze to follow our simple guide to Halloween bliss.

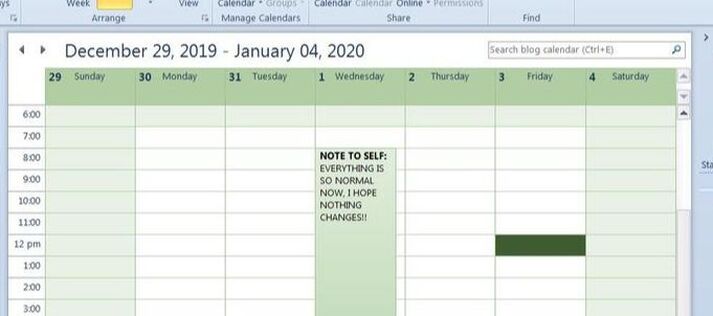

Of course, there’s no risk this year if you simply put a sign on the door to announce that you aren’t giving any candy. After the panic buying and shortages in March, most parents I know are keeping their soap and toilet paper locked up, so you’re safe. Isn’t this the holiday you’ve always wanted anyway? Just you, a big bowl of candy and, well, what else do you really need? Halloween should always be this way, even if we’re not lucky enough to have a pandemic next year. What great insights will we offer for Thanksgiving and Christmas? You'll never know unless you subscribe by clicking right here right now.  What would you think if I told you I was an internationally recognized philanthropist? Or, maybe, an award-winning author? What if I described myself as a private investor or a business mentor? And what would you think if I simply said I’m retired and I left it at that? It’s pretty easy to put people into boxes, reacting to the first descriptors used to define their place in the world. Snap judgments are hard-wired into our survival instincts, which is a great benefit when a lion walks into the kitchen, but not quite as valuable when we’re trading factoids at a cocktail party. (Cocktail parties! Remember those? Sigh.) Most of us add new descriptions to our social resume as we progress through life, engage with family, navigate a career and become whoever it is we plan to be when we grow up. All these new identities and new milestones provide depth and texture to us, to our personalities, and to our social capital. They make us more interesting and more complete, if we take the time to learn anything on our journeys. And then, just as we become our most multifaceted and fully developed selves, we give up. We start talking about ourselves in the past tense, as if we’re drafting our obituaries. I’m a former accountant. I used to be a sales rep. I was once a teacher. I find it just a bit depressing. Everyone has an interesting story or two about their well-earned scars, and everyone is doing something today, yesterday, tomorrow, that forms the nucleus of a new adventure. Despite that rich tapestry, so many people I meet will announce that they’ve given up on being interesting, that all they have to offer of relevance is a job they held. Once. A long time ago. It’s as if there’s nothing we have to offer the world other than our labor and some form of industry expertise. We are our jobs and, when we leave our jobs, we are nothing. Our only claim to relevance is an expired key card from the law firm and, maybe, a part-time gig as a “consultant.” Perhaps it’s my own fault. I still ask people what they do and that generates a default response about how they make, or made, money. I need to get more creative about my introductory conversations. Maybe things will get more interesting if I ask… What was your favorite trip ever? What’s the craziest thing you’ve ever seen face to face? What’s the strangest answer you’ve ever received when you asked someone what they do for a living? One of the positives with questions like these is that I’m unlikely to hear about work. That’s good, because I really don’t want to know about their jobs, or their former jobs, or why they think of themselves as has-beens. “What do you do?” turns out to be a conversation stopper, not a starter, especially when it turns into what someone doesn’t do anymore. Asking people what they do is pretty pointless and likely to make them feel bad about their former glory. If I want better answers, I had better come up with some better questions. The big question we’re all asking at Dad Writes is whether you’ll become a subscriber by clicking here for our weekly insights. So, whaddaya say?  I know a couple who finally put away enough money to retire, so they sold their business and invested their sweat equity in the stock market. It was 2008, just before the crash. I ran into the wife earlier this year, still working part-time at the store she used to own and making plans to retire, again. She’d had a dozen years to adapt to her “new normal,” knowing that her old normal, the one that seemed absolutely certain in 2008, isn’t coming back. I think about her and her husband whenever people tell me about their hopes for returning to normal after this pandemic subsides. Normal, the one we were counting on in January of this year, isn’t coming back. On one level, we should recognize this as a fundamental truth. We tend to think of the current situation as the norm, or think back to a specific point in time as the benchmark for normalcy, but the only real normal is change. We, the world, are eternally in flux. I have some friends who believe the pandemic is a hoax that is being promoted to affect the presidential election, so they also believe it will fade into the background on November 4. I have other friends who think access to a vaccine will enable us to reboot the economy to our bookmark date of January 1, 2020. I know more than a few guys who seem to think we can return to normal by reopening everything and getting to herd immunity as quickly as possible, because it’s worth the trade-off in lives lost. Me? I think they are kidding themselves. Too many people, and organizations, have been changed by this for us to bounce back to the days of yore. When/if there’s a vaccine, for example, an above-average percentage of the population won’t take it at first. I am included in that group. I get my flu shot every year, but the race for a vaccine has become so politicized that I can’t find my way to trusting whatever gets approved first, or second, or maybe even third. All the political wrangling has achieved its goal of causing distrust, but that distrust translates into an extended crisis. I probably will wait six or eight or twelve months before taking any vaccine and that means I will wait six or eight or twelve months before I dine indoors or go to a casino or fly on a plane. How many people will skip the vaccine? Certainly, the people who refuse to take any vaccines already will sit this one out, but millions more will wait a long time before they accept that the vaccine is safe. Whether it’s 5% or 10% or 0.8% of the population, this caution will slow our economic recovery and delay our return to “normal.” Herd immunity, if it could be achieved for this particular virus, might remain out of reach as the vaccinated cohort makes up too low a percentage of the population. Meanwhile, dozens of industries and about a million companies will need years or decades to recover, if they manage to survive at all, because their profit models are based on cramming a large number of people into a small space for an extended period. That includes restaurants, bars, mass transit, airlines, casinos, hotels, health clubs, sports arenas, convention centers, churches, schools, office buildings, theaters, and probably a few dozen I haven’t thought about. Well-capitalized companies, which tend to be larger, will tend to be the survivors, while mom-and-pop stores fail, accelerating the concentration of wealth and commerce that has been underway for decades. As small businesses fail, their owners might simply decide to retire, increasing the impacts for the Social Security system. On the other end of the working years, millions will discover that their career paths have been washed away by social distancing, online commerce and working from home. Whether it’s the people who cleaned the now-empty offices or the chefs who have no restaurants, the disruptions will be significant for enough people that their social and financial progress might be delayed for an extended period. Changes that are already under way, such as the rise of online shopping and communication, will accelerate during this period of reduced personal contact. Changes that might have taken another 5-10 years might be compressed into one or two, making any disruptions more rapid and severe. However the world changes, and changes us, the ripples will be sustained, like a thousand butterfly effects competing for influence. It’s impossible to pinpoint the exact impact of each shift, which is a truth that applies to every change we encounter, but we know enough from prior upheavals to recognize that shifts will occur. Every day is a new normal, a new life, and the only thing we can know for sure is that we’re never getting back to the way things were in the time before. In a world of upheaval, the only real constant is the incredible value of a subscription to Dad Writes. Just click here to become a subscriber and your life will always be both new and normal. |

Who writes this stuff?Dadwrites oozes from the warped mind of Michael Rosenbaum, an award-winning author who spends most of his time these days as a start-up business mentor, book coach, photographer and, mostly, a grandfather. All views are his alone, largely due to the fact that he can’t find anyone who agrees with him. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed